In 1912, radio technology was rather new.

The Marconi Company had made most of its living selling radio gear to ships, and the Titanic ws one of the few that had bought into the tech. You have to think of radio in 1912 as you might the web in 1992 - barely known, barely used and barely understood.

Jack Philips was the Senior Wireless Operator aboard the RMS Titanic on her maiden voyage. He was joined by Junior Wireless Operator Philip Bride. As the whole concept of wireless was so new, so were the ranks.

On the evening of April 14th, the night the Titanic struck the iceberg, Philips was busy on the wireless, sending message to Cape Race.

Cape Race is a tiny peninsula on the southern tip of Newfoundland. This was considered the first point of entry for wireless traffic in the new age of radio transmission. In 1904, the first wireless station in North America was constructed at Cape Race.

The Titanic was, as you probably know from the movie, filled with some of the wealthiest passengers from Europe and America. They had both personal and business messages they wanted to transmitted to New York, via Cape Race, and so it was both Phillips and Bride's primary jobs to make sure those messages were transmitted by wireless.

In those days, radio was thought of more as a kind of 'through the air', point-to-point transmission process; a bit like a telephone without the wires. Hence: radio telephony.

Meanwhile, back in the North Atlantic, and only 10 or 12 miles ahead of the Titanic, lay the Californian, another ship crossing the North Atlantic. The Senior Wireless Operator aboard the Californian was Cyril Furnstone Evans.

The Californian had come to a dead stop in the Atlantic because of ice fields, and having stopped, Captain Stanley Lord entered the radio room and told Evans to radio all ships in the area to also come to a dead stop because of the ice fields, which he did.

In later, more sophisticated radio technology, it would be possible to limit the signal to a rather narrow band of the EM spectrum. But in 1912, both Evans and Phillips were working with what was called spark gap wireless sets. As a result, the radio transmission bled across the spectrum. As the Titanic and the Californian were in close proximity to one another, the transmissions from the Californian overwhelmed all other signals, both incoming and outgoing from the Titanic.

When Evans radioed his danger warning about ice floes ahead, Phillips transmitted back: "Keep Out! Shut Up! I am working Cape Race!"

Cape Race, being quite far away had only a faint signal. The warnings from the Calfornian were drowning out the passenger's messages to Cape Race.

Evans listened for a while longer, than shut off his equipment and went to bed.

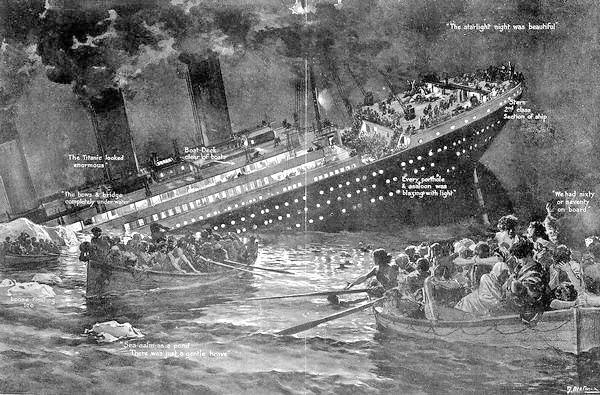

At 11:40 PM, the Titanic struck its iceberg.

Bride had awakened and joined Phillips in the radio room, where they were soon joined by the Titanic's Captain Smith who instructed them to start sending out the distress call, and gave them the Titanic's position.

Of course, the Calfornian never heard the signal. The wireless had been shut down.

Bride and Phillips continued to transmit their SOS, (some say it was the first use of SOS - the old distress signal CQD having just been replaced) until water filled the radio room.

Evans, aboard the Californian, never got the signal. But David Sarnoff, a young employee of The Marconi Company, working in a small radio demonstratoin display in the window of Woolworth's Department Store did.

He was the first person in America (and indeed in the rest of the world) to learn that the Titanic was sinking.

Sarnoff, realizing the immense power of radio, NOT as a substitute for the telephone, but rather for something entirely new - the idea of BROADCASTING one signal to millions of people, would go on to found both RCA and NBC as well as pretty much invent the broadcasting industtry.

Bride would survive the night. Phillips was never seen again.

Evans continued to work for The Marconi Company and died of a heart attack in 1959.