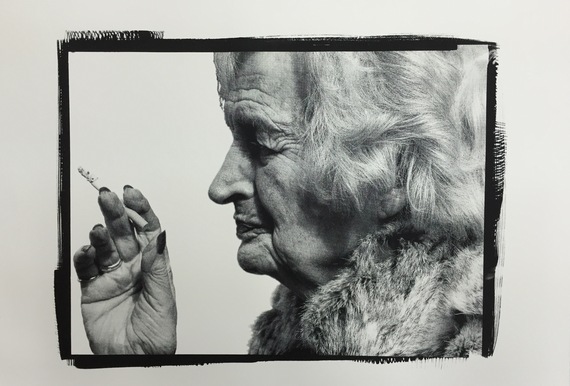

Ann Pattenden - Silkscreen print - ink on canvas - 36x48

In a piece in the NY Times today, Rob Walker comments on the 'return of the physical'; the fascination with all things analog - from printed books to vinyl records to over the air TV broadcasts and rabbit ear antennae.

As far back as 1982, at the very dawn of the digital age, author John Naisbet wrote in Megatrends that the arrival of a digital world would also cause a love affair with all things physical - fountain pens and manual typewriters. As our world becomes less and less real - less and less physical, there is a natural draw towards doing things with you hands - towards 'crafting' the product yourself.

I can relate.

I have spent the past 30 years in a very high-tech world - video, television and online - live streaming, 360 degree VR, you name it.

I got into this business a long long time ago because I was a photographer, or at least I wanted to be one. I was mesmerized by images and the process of collecting them. There was a kind of intimacy about it. While I carried that notion of photography to video (I launched my VJ concept on the premise of television journalists working as Magnum photographers did - on their own), I never lost my passion for photography itself.

Photography, however, changed.

Like everything else, it was touched and altered by the 'digital revolution'. Physical film (we used to buy it in bulk and load our own film canisters in the dark) was replaced by digital cards holding hundreds of images. The act of printing the photographs - endless hours in the darkroom watching the images appear in a series of chemical baths - was replaced by a few simple manipulations on a computer.

The results were generally better, but the experience was not.

At first I thought I would simply go back to film, build myself a darkroom in my basement, find my old enlarger and make photos the old fashioned way. This did not work - and not just because living in a Manhattan apartment, I don't have a basement. Corrupted by my exposure to digital, I found the process, frankly, frustrating.

So a few years ago, I decided to take it even further. Thanks to a Christmas present from my wife (and a few classes at Williams a century go or more with Tom Krenz), I began to take very high resolution photographs of people, but print them in ink, by hand, as a silkscreen print. She got me studio space at LESP, the Lower East Side Printshop in Manhattan.

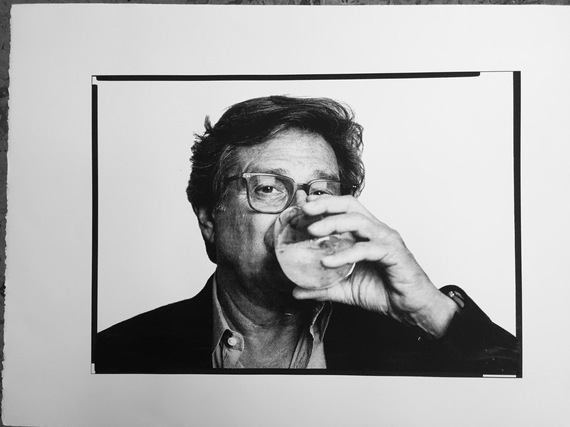

Bradley Mendelson - Silkscreen print - ink on paper - 36x48

The process is laborious - and extremely physical. The photographic image, taken with a digital Hasselblad, so the file is VERY big, is then transferred to a halftone film - (it either goes to black or white - it's how newspaper photos were published a long time ago) that is the size of the final print. That image is then 'shot' onto a chemically coated silkscreen - sometimes several with different exposures - and the screens are then put in a press and I push ink through them onto a large piece of paper to make the prints.

It is very satisfying.

It brings back a connection to the process of capturing and 'making' the image that the digital, push-button world took away. Even though my photographic prints were quite good (you can play with them in photoshop all day long until they are perfect, or nearly so), the better they got by manipulation, the more I felt I had less and less to do with them - if you know what I mean.

Manhandling the giant screens, firing up the tungsten lamps to expose the screens, climbing up on the press to pour in the ink and drag the squeegee - all of that made me feel like I was 'doing' something; something more than just dragging around a cursor.

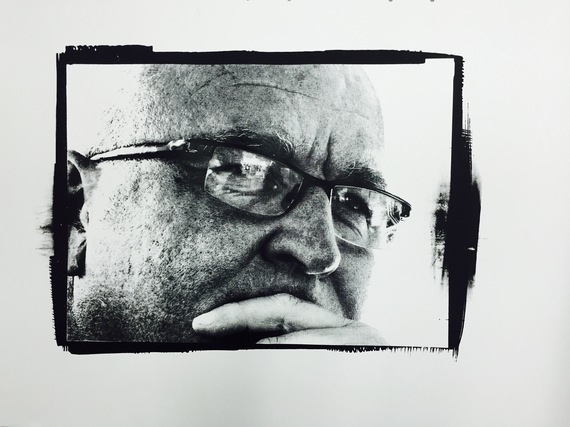

Andrew Measom - Silkscreen print - ink on paper - 36x48

Since the first caveman pounded a rock against a piece of flint to create a sharpened edge, we have been a species of toolmakers. We have created our world with our own hands - whether it was as a wheelwright, a bricklayer, a carpenter or a farmer. We got out hands dirty and we ate our bread by the sweat of our brow (Gen. 3:19)

Today, very few of us sweat over our laptops or our tablets or our iPhones. Probably that is better, but there is some strange satisfaction, some fascinating and deep contact with who we are buried in our DNA that resonates with physical labor to create and craft a product.

Last year, Lisa gave me a 100 year old manual typewriter for a Christmas present. The clatter of the keys, the ding of the bell, the physical bang and slam of the return of the carriage after each sentence gives me the same sense of accomplishment that somehow, hitting 'send' simply fails to deliver.

Lisa's Eye - on exhibit last year at the Chashama Gallery in Harlem